Data centres appear to be the new big thing for the world’s electricity grids, and Australia is likely to be no exception. There is huge debate about the scale of growth, exactly how hungry for power and how flexible they will be, and whether this is a good thing for society or not.

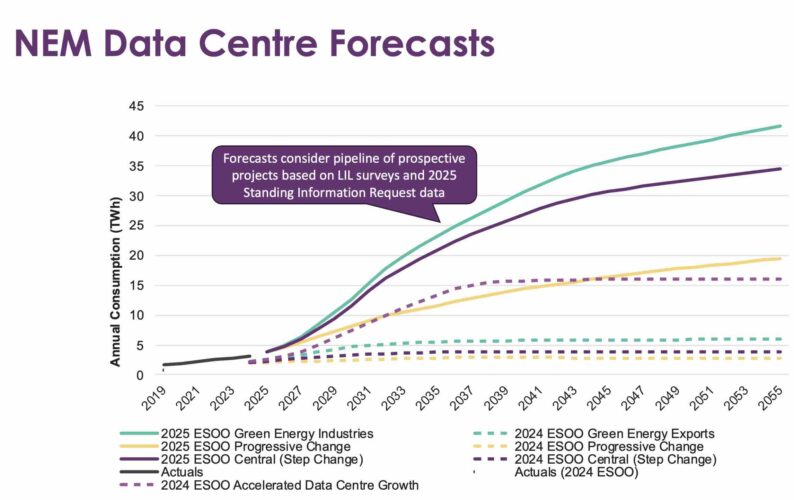

But there is no disguising their potential impact, and the need for grids to get ready. And recently updated forecasts for Australia’s main grid suggests there could be 40 terawatt hours of data centre demand by the time the country is due to reach net zero in 2050 – equivalent to about one fifth of the grid’s total current output.

The new forecasts have been published by the Australian Energy Market Operator as part of its Forecasting Reference Group.

They give early insight into the calculations to be used as it prepares its 10-year demand forecasts, to be released next month, and the updates to its longer term planning blueprint for the grid later this year

What’s interesting about the latest data is the massive increase in data centre demand forecasts from just a year ago, and over the shorter term, with predictions of 15 gigawatt hours of data centre load by 2030.

That, of course, has implications for Australia’s grid, and its ability to reach its target of 82 per cent renewables by the end of the decade.

Notionally, a big increase in demand makes that the country’s state and federal renewables targets will be tougher to achieve, given there is more demand to serve and that will require more wind and solar than previously assumed.

But in some ways it may actually help. Tens of gigawatts of proposed wind and solar capacity have found themselves stranded, and effectively excluded from the grid, because the infrastructure planned for many new renewable energy zones is simply not big enought.

This is the case in the south west renewable energy zone in NSW, and clean energy investors say the same problem is going to emerge in Victoria, under its newly released transmission plan.

Some developers, including Engie, have suggested building data centres in these regions could unlock new wind and solar capacity because their output can be used to satisfy local demand, and will not need bigger transmissions to transport them to load centres far away.

ITK principal David Leitch, also co-host of Renew Economy’s weekly Energy Insiders podcast, delves deeper into the possible matching of data centre demand and the wind and solar project pipeline, particularly in the Riverina, in this piece here.

Interestingly, one of the big new players in the battery storage market, Ampyr Energy, led in Australia by former AEMO senior executive Alex Wonhas, says its Singapore-based backers also have interests in data centres, and may seek to combine the development of those projects in local grids.

“Our investor, AGP, is also building a data center business, and so we have the opportunity … of co-locating a data centre with a battery that unlocks …. behind the meter opportunities at a scale that is, you know, fairly unique,” Wonhas says in the latest episode of the Energy Insiders podcast

What is clear from the work of the Forecast Reference Group is the ability of wind and solar heavy grids to draw interest from industry, including data centres, attracted by the prospect of cheaper power deals and zero emission supplies, a critical component in international trade and contracts.

This, of course, is completely contrary to the usual conservative claptrap that renewables will be the death of industry, but most people know that the politicians and Murdoch commentators sprouting this nonsense are simply parroting the talking points of the fossil fuel industry.

ElectraNet, which supplies the backbone of Australia’s most advanced renewable grid, South Australia, has been clear about the number of new load enquiries it has been fielding as the result of the number of energy-intensive industrial customers attracted to the state’s world-leading penetration of wind and solar.

The FRG information points to a doubling in electricity demand from large industrial loads in South Australia over the coming decade, and that is excluding green hydrogen, which has probably been relegated to the possible and the maybe rather than the probable assumed a year or two ago.

“Even if we discount some of this as tyre kicking from prospective data centre developers across different NSPs (network providers), the growth is significant and steep with around 15 TWh in 2030 and over 25TWh by 2040, the Clean Energy Council’s Christiaan Zurr.

“The potential speed of data center development is what makes this a key variable to watch. Anecdotally, data centers can be up and running in a few years, or less.

“Further, the type of data and processing capacity in a data center also influences their power consumption. The question is whether the supply side can keep up with the scale, speed and uncertainty of their development.”

A flip side to the interest in data centres is that their hunger for power may lessen concern about a new problem emerging for AEMO, that of minimum demand.

The market operator has previously raised concerns that the growth in rooftop solar PV – still running at up to 3 GW a year – is eating away grid demand in the middle of the day, to the point where AEMO has flagged “emergency backstops” such as cutting off rooftop solar, or forcing batteries to be on standby, to maintain grid security.

But the new forecasts suggest that the growth in data centre interest – along with electrification and the growth of large industrial loads – will reduce this problem significantly.

Indeed, AEMO has upgraded its minimum demand forecasts in Victoria, NSW, Queensland and South Australia and says that it will decline at a slow rate than forecast last year.

In some states, like Queensland, minimum demand is no longer forecast to go negative, while in NSW it may not happen for another decade, nearly five years later than previously forecast.