Australia’s grid continues to demonstrate that rapid growth of renewable energy does not mean a guaranteed drumbeat of blackouts, or unmanageable system costs.

This has been obvious to many of us for a long time, but it bears repeating, given the recent blackout in Spain and the way that event re-triggered debate and discussion around the management and integration of high volumes of renewable energy in power grids.

In fact, two recent reports (one from the Spanish government and another from the grid operator) both confirm that the reasons behind the blackout were boring, complex and multi-factorial, mostly relating to the management of voltage fluctuations, and featuring failures from a large variety of generation types on the Spanish grid (coal, hydrol, solar, nuclear etc).

This is despite a very large number of anti-renewable forces attempting to blame the event on a lack of ‘inertia’ – a grid service primarily supplied by thermal generators like coal, gas and nuclear.

Australia’s main power grid, the National Electricity Market (NEM) has risen from 16% renewables to 41.1% renewables, from late 2016 to June 2025. And a new health check from the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) examines how that grid’s stability has been managed over that time period.

“The Panel found that the NEM has continued to maintain high levels of reliability. Consistent with previous years, there was no unserved energy (USE) in FY2024,” it says.

USE relates to blackouts caused by problems with either power generation or large transmission infrastructure (as opposed to issues with local power lines, which cause the vast majority of blackouts).

The AEMC shares a slide deck and a pack of Excel charts, and below, I’ve extracted the key graphics that tell the story of how Australia’s power grid has maintained stability even as non-thermal, non-synchronous generation has increased massively.

Unserved energy remains at zero

Every year, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) releases its “electricity statement of opportunities”, or ESOO. That report aims to trigger investment in new infrastructure.

It does this by modelling whether or not generation and transmission is being built at a sufficient rate in the near future, and if not, warning of blackouts due to insufficient ‘unserved energy’. The warnings are always dire, and often reported with a frantic and exaggerated tone in mainstream media outlets.

What remains completely unreported is the fact that those blackouts almost never materialise, because the construction of new energy infrastructure in Australia remains relatively healthy (and in the past decade, power demand has not risen as dramatically as once envisaged).

So despite the frequent warnings of high USE (blackouts), the actual measured number of blackouts relating to insufficient large-scale infrastructure looks like this:

In this piece, which I published in August last year, I compare these ‘actual’ measures of blackouts to the various historical forecasts and projections. It looks roughly how you would expect: the gloomy prophecies are never fulfilled.

This doesn’t mean we can relax when it comes to ensuring new wind, solar, batteries and transmission are built at pace.

But it definitely highlights how media reportage is badly skewed: the simple good news that there hasn’t been any generation-related blackouts in four years simply doesn’t exist anywhere. It is a shame that the grid operator only really gets attention when things go wrong.

Lack of reserve notices are easing

A “lack of reserve” notice occurs when the grid operator either expects there’s a dangerously reasonable chance of blackouts due to a lack of generation capacity (LOR1 and LOR2), or to declare that blackouts are actually occurring for these reasons (LOR3).

As you can see below, “actual” load shedding has almost never occurred, but the warnings (either actual warnings of the forecast of an upcoming warning) are relatively frequent. But the number of these warnings decreased in every region in FY24, and many of the ‘actual’ notices tended to manifest in coal and gas heavy grids (NSW and QLD):

The distribution network is doing better

You wouldn’t be able to guess this from media coverage, but the majority of blackouts experienced by consumers relate to the distribution network – that is, the poles and wires you see on your local street:

But even this is improving – two different measures show roughly the same long-term trend towards a decrease in locally-caused blackouts for consumers:

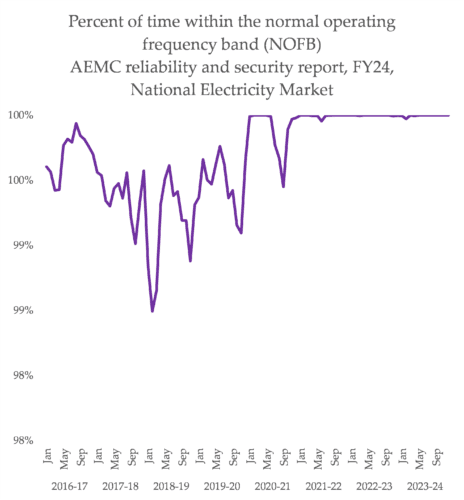

Frequency has improved significantly

Power grids need to maintain ‘frequency’ at a very specific level, with very narrow bands for tolerance outside of these zones.

Sometimes described as the ‘heartbeat’ of the grid, any excursion outside of tolerance results in blackouts as generators and demand disconnect to protect themselves, or worse, actual physical damage if those protection systems fail.

It was ultimately a rapid frequency excursion outside the range in South Australia in 2016 that was the ultimate final step in the ‘system black’.

And the core criticism of renewables is that their failure to help maintain this frequency through a lack of ‘inertia’ (simply, the ability for large spinning generators to tweak output up and down quickly thanks to the willingness of spinning things to keep spinning).

Since 2021, time spent within the narrow bands has been at nearly 100% – and before that, the vast majority of time was within the bands (note the truncated X-axis below):

Note that the data above refer to the mainland – Tasmania’s performance is far worse: “Basslink interconnector operations continued to be the primary cause of extended frequency excursions in Tasmania, with events attributed to flow reversals, import limitations, or scheduled maintenance outages”

Batteries are helping to keep a lid on system costs

Not only has the broader cost of managing frequency fallen significantly since the start of 2024, it seems to be linked closely to the establishment of a new category of frequency response, where the ultra-fast response capabilities of lithium ion battery systems are used to ‘tweak’ generation with a speed that old, traditional ‘spinning’ generators can’t manage.

As AEMC highlight below, batteries are dominating this market, particularly the faster ‘1 second raise and lower’ services:

A related slide shows how the decrease in FCAS costs is the main contributor to stable overall system operating costs:

A lot of this is good news, but it shouldn’t engender complacency about the future. There is a good chance Australia’s power demand growth will be higher than expected in the near future, related to climate impacts such as summer heatwaves, or the tech industry’s data centre construction frenzy.

Not only does this make the job of decarbonisation much, much harder, it also makes the possibility of dire forecasts higher. Australia’s renewable energy industry is still growing, but is it enough to achieve decarbonisation goals?