An electrolyser that collects atmospheric water vapor, including from seemingly “bone dry” air, and converts it into hydrogen has been developed by Australian and international researchers.

The breakthrough, led by a team at the University of Melbourne, paves the way to produce renewable hydrogen without the need to consume precious drinking water.

In a study published in Nature Communications, the prototype device, which absorbs moisture from the air and splits it into hydrogen and oxygen, is powered by solar and wind.

The researchers test their prototype electrolyser under a range of relative humidity levels, going as low as 4%, and find that it steadily produces high purity hydrogen – in one case for a period of more than 12 consecutive days – without any input of liquid water.

This is important, because current hydrogen electrolyser technology usually requires access to increasingly limited resources of pure water, whereas this device – the researchers say – could be scaled to provide fuel in remote, arid and semi-arid regions.

For example, the team notes, even in the Sahel region in western and central northern Africa has an average relative humidity of about 20%, while the average daytime relative humidity at Uluru in the central desert of Australia is 21%.

How does it work?

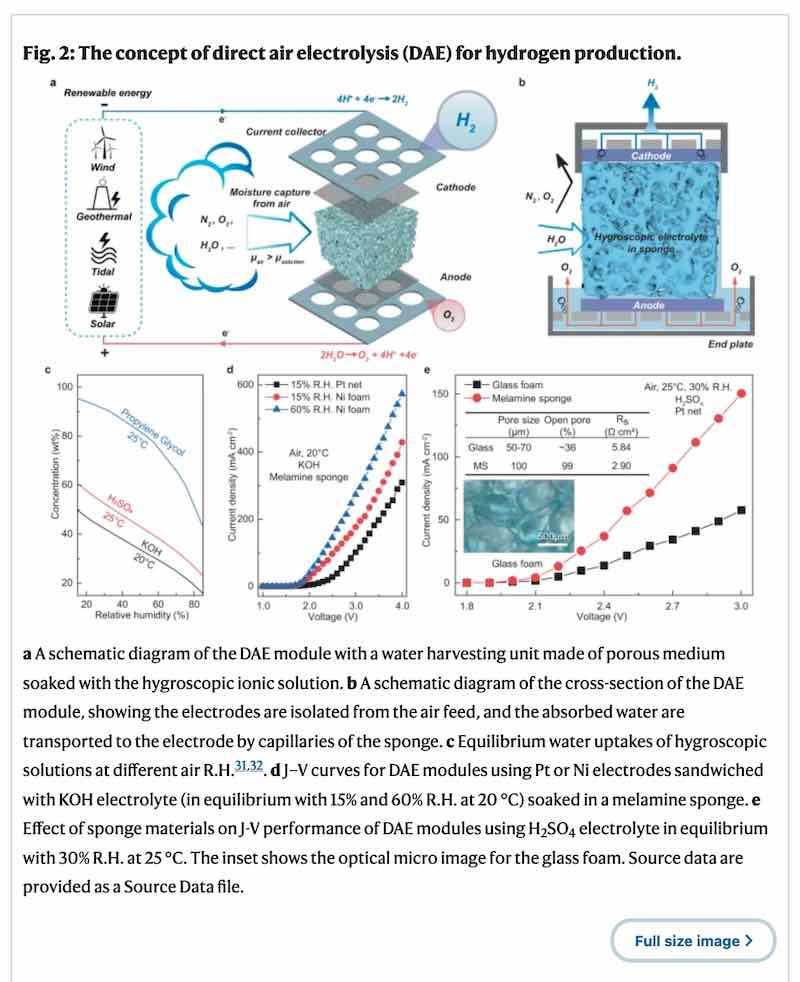

The team’s Direct Air Electrolysis (DAE) module is made up of a water harvesting unit in the middle and electrodes on both sides, paired with gas collectors and integrated with a renewable power supply – in this case, a lot of the testing was done using solar.

A porous medium such as melamine sponge is then soaked with a hygroscopic (or water attracting) substance to absorb moisture from the air via the exposed surfaces.

The team tested a range of hygroscopic materials, including potassium acetate, potassium hydroxide, and sulfuric acid and found that all three materials spontaneously absorbed moisture from the air and formed ionic electrolytes.

It found that the direct air electrolysis modules were able to produce hydrogen gases successfully at a very low level of relative humidity, or at a higher humidity for a period of more than 12 days, with a continual supply of air and power.

A solar-driven prototype with five parallel electrolysers has been devised to work in the open air, achieving an average hydrogen generation rate of 745 L per day−1 m−2 cathode; and a wind-driven prototype has also been demonstrated, the team says.

What the researchers say

“Few studies have been trying to mitigate the water shortage for electrolysis,” say the authors of the report, led by Jining Guo, Yuecheng Zhang, Ali Zavabeti, and Kaifei Chen.

“Direct saline splitting can produce hydrogen, which, however, faces a serious challenge of handling chlorine byproduct,” they add, noting that other methods trialled have resulted in low purity hydrogen.

“In this work, we corroborate that moisture in the air can directly be used for hydrogen production via electrolysis, owing to its universal availability and natural inexhaustibility – there are 12.9 trillion tons of water in air at any moment,” the report says.

“Considering …materials such as potassium hydroxide, sulfuric acid, propylene glycol can absorb water vapor from a bone-dry air, here, we demonstrate a method to produce high purity hydrogen by electrolysing in situ hygroscopic electrolyte exposed to air.

“This work opens up a sustainable pathway to produce green hydrogen without consuming liquid water.”