Australia must rapidly decarbonisation while delivering affordable, reliable power. Renewable Energy Zones (REZ) will be important in doing this.

A REZ is a cluster of generators sharing transmission infrastructure to provide a lower-cost and faster way of delivering new, renewable generation into the system.

Despite their obvious benefits, REZs haven’t yet been delivered.

A key reason is rules and regulations – collectively, a relic of last century’s energy grid – that don’t support building transmission infrastructure ahead of new generation and don’t require generators to cover some of the cost of the regulated transmission infrastructure they need.

The main barrier to fixing this problem is narrow thinking by national energy rule makers.

The result is inefficient transmission investment that lumps consumers with unnecessary and unfair costs and risks, and slows the deployment of renewables.

Current reform solutions won’t fix the issues

For years market bodies have been toying with how to deliver the surge in transmission required to connect large-scale renewable generation and storage, but have avoided solutions that require generators to pay their share of new transmission assets.

In reform processes such as the Australian Energy Market Commission’s (AEMC) Coordination of Generation and Transmission Investment (COGATI) – the most obvious place to deal with REZs – the AEMC has seemingly taken the view that investors can’t, or won’t, build new generation if they have to cover the cost of their share of new transmission infrastructure.

This view doesn’t reflect the needs and opportunities of the market or the future energy system.

The recent announcement by a partnership of generators to self-fund a major transmission line to connect a prospective renewable energy hub in NSW shows generators are willing and able to pay their way for infrastructure optimised to meet their needs.

This is hardly surprising.

Connecting generators have a strong interest in REZ transmission infrastructure that provides them with greater certainty of connection cost, reduced risk of being constrained, and better Marginal Loss Factors (MLF).

The 2020 Integrated System Plan (ISP) identifies 18 transmission network investments, and a collective cost of many billions of dollars, in the optimal development path of the NEM.

Failing to require generators to pay their share means the cost of these investments will be borne by consumers who are not the only beneficiaries and who have no ability to control the risks of assets being underutilised.

The current arrangements don’t work for generators either; they are only able to make these beneficial investments outside the regulated network.

As one of the partners in the recently announced self-funded transmission project said, “Australia is not going to achieve any of its current renewable energy or decarbonations goals with the current Regulatory Investment Test for Transmission process”.

Notably, failing to require large-scale generators to pay for their share of transmission network investment is inconsistent with the AEMC’s own treatment of small-scale generation in the distribution network.

In its recent draft determination for access and pricing for Distributed Energy Resources, the AEMC proposes to allow network businesses to charge solar customers for their impact on the grid.

Putting aside whether or not that is fair, the internal inconsistency, that network costs for household solar shouldn’t be cross-subsided, but networks for solar farms should be subsidised by energy users, is striking.

A comprehensive model for sharing risk and cost

Since 2017, energy consumer advocate the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) has developed and proposed a model for funding REZs that shares the risks and costs of developing them between generators, consumers and transmission investors (who could be governments, generators, new private investors or existing transmission businesses), rather than just consumers.

It offers a fairer, complete solution for how costs and risk are allocated for shared transmission to support REZs.

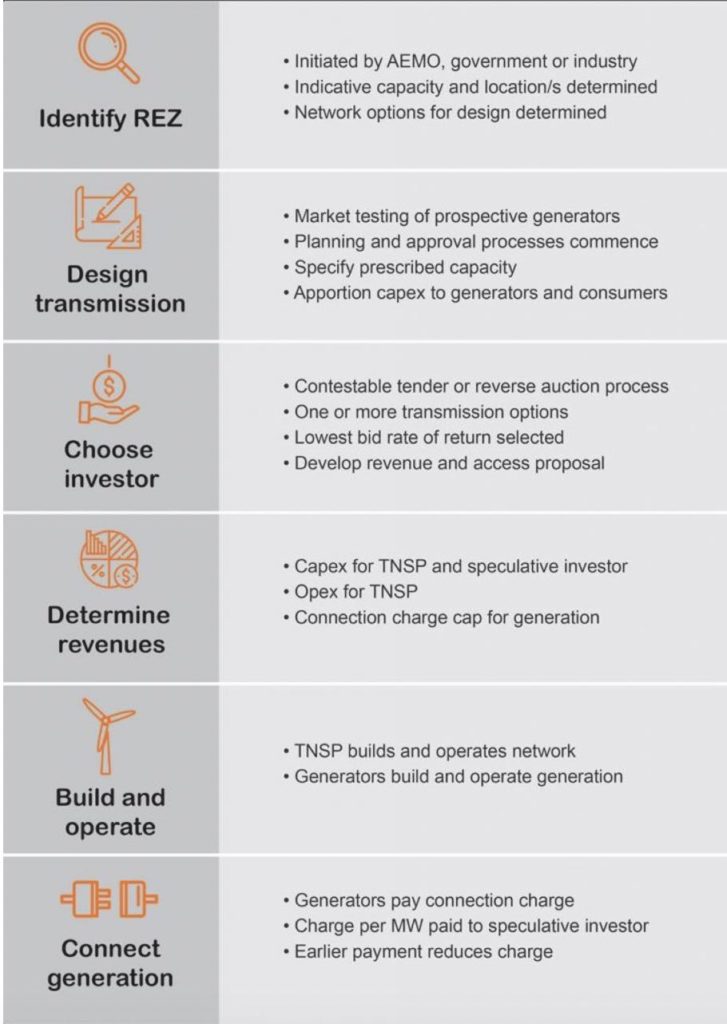

The process for planning, delivering and connecting to a REZ under PIAC’s model is summarised in the diagram below.

Under the PIAC model, generators are better off than they would be connecting outside of a REZ under current regulatory frameworks, with better and more certain capital costs in the short term and revenue in the long term.

They are rewarded for connecting early through lower access charges, or can connect later if they prefer. MLFs and access are more predictable.

At the same time consumers aren’t hit with the cost of billions of dollars in new transmission, and existing regulated transmission businesses aren’t exposed to any more risk than they face under the existing regulatory framework.

You can read more about the PIAC model and its benefits here.

It’s clear the current regulatory arrangements must fundamentally change to be fit for the purpose of building new transmission for renewables.

Until now, the AEMC has promoted inadequate incremental changes, along with unpopular ideas like Financial Transmission Rights, rather than comprehensive reforms to transmission cost and risk sharing for REZs.

In response, states like NSW and Victoria are going their own way to make REZs a reality, and the dream of national consistency for transmission access grows ever most distant.

With the Energy Security Board’s attention now on REZ reform, it has a choice: continue down the AEMC’s path of minimal adjustments to the current framework, or make comprehensive reforms that reflect the market we’re in today and the clean energy system we need in future.

Craig Memery is policy team leader at the Public Interest Advocacy Centre.