If you thought the price of petrol was expensive now, imagine what it would be if all its environmental and human health impacts were factored in. According to a new study from Duke University in the US, it would be around $1 a litre, or nearly $2,000 a year for an average petrol car.

The study by Drew Shindell, professor of climate sciences at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, says the cost would be around one quarter greater for diesel vehicles. On the other hand, electric vehicles have a social cost of less than half, even if the EV is charged by coal-fired electricity.

According to Shindell, a coal-fired EV would have a social cost of nearly $1,000 a year, a gas-fired EV around one third of that, while an EV charged with renewable energy – or, in the US, nuclear – would have negligible social cost.

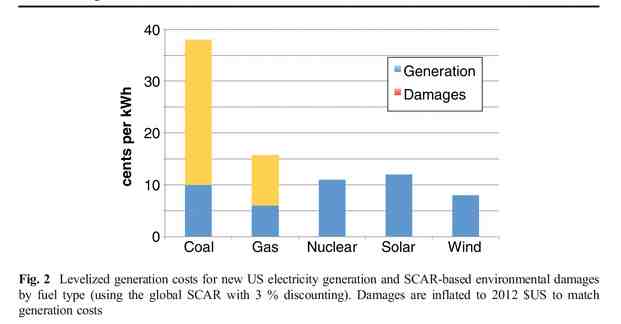

Shindell also factored in the social cost of electricity, whether it be coal-fired, gas-fired or from solar and wind power. Using generation data from the US energy department, albeit two years old and a bit out of date on the cost of solar and wind, Shindell used this table to show how the social cost of coal is nearly four times its generation price, and the social cost of gas is more than two times its stated generation cost.

Of course, in the US, none of these costs are factored into the price of those services, be they electricity or fuel for the cars. Neither are they in Australia and anywhere else without a carbon price of specific environmental levy.

“We think we know what the prices of fossil fuels are, but their impacts on climate and human health are much larger than previously realised,” Shindell said. “We’re making decisions based on misleading costs.”

Shindell said his study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Climatic Change, provides policymakers with a more accurate framework for estimating the costs of a broad range of health, climate and environmental damages linked to emissions from fossil fuels, industry, biomass burning and agriculture.

He said because markets don’t place a price on most atmospheric emissions, polluters typically pay none of these costs. But society picks up the tab in the form of increased risks of premature death or illness caused by air pollution, higher healthcare costs, lower crop yields, missed work and school days, increased insurance damages from floods and other extreme weather events linked to climate change, and other social costs.

“Putting values on many of these social costs can be challenging because there are so many factors in play,” Shindell said.

The comparative framework devised by Shindell to calculate these costs is built upon a widely used methodology introduced in 2010 to help the U.S. government determine the social costs of carbon.

Shindell’s models draw on methodology used by the US government to determine the social cost of carbon, and extended to include damages from potent but short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) such as methane and aerosols, as well as longer-lived greenhouse gases such as nitrous oxides.

“Looking at electricity, for example, the US Energy Information Administration estimates generation costs per kilowatt hour of power to be about 10 cents for coal, 7 cents for natural gas, 13 cents for solar and 8 for wind,” Shindell said.

“Not surprisingly, the US has seen a surge in the use of natural gas, the apparent cheapest option. However, when you add in environmental and health damages, costs rise to 17 cents per kilowatt hour for natural gas and a whopping 42 cents for coal.”

“There is room for ongoing discussion about what the value of atmospheric emissions should be. But one thing there should be no debate over is that the current assigned price of zero is not the right value.”